03/17/2023 – Revisions to Through Both Eyes.

It has been a while since I publish Through Both Eyes. It was fun to write and has been enjoyed by many readers. Based on reader feedback, I have decided to revise the novel by cutting certain sections that slowed the story’s progress. I have designed a new and more pleasing cover and replaced the original version at Amazon.com with a second edition. I think you will like the improvements.

03/15/2023 – March update.

Will winter ever end this year? It was cold and rainy this morning. I thought when the Purple Martins returned, the winter was over. But the martins have been back for more than a week. The cardinals and titmice are singing, and the Turkey Vultures are migrating. The cowbirds and Red-winged Blackbirds are back. I’m ready for summer.

Looking around our website, you’ll discover that Karen and I have been developing material for the new Amazon Kindle Vella platform. So far, we’ve started a suspense/thriller series called “The Howler Monkeys,” a series of essays based on Karen’s writing called “Brush Country Rambles,” and a series named “Backstories.” Please check them out HERE. They’re fun to write; hopefully, you’ll find them entertaining to read.

Manfreda maculosa, the host plant of one of the rarest butterflies in the world, in bloom at Pauraque Ridge

04/01/2021 – What’s a Manfreda?

April 1st, 2021, is the first day of the National Butterfly Center’s Manfreda Survey. What’s a Manfreda, you ask? Manfreda is the genus of a south Texas plant that is the host for one of the world’s rarest butterflies, the Manfreda Giant Skipper. It was considered by some to be extinct, but a small population (at an undisclosed location in south Texas) has recently been found. The National Butterfly Center has initiated a new citizen-scientist project to help document the host plant’s occurrence and possibly discover other populations of the rare skipper. We have the wild host plant here at Pauraque Ridge and know of different Bee County locations where Manfreda grows. We have joined the effort to rediscover the Manfreda Giant Skipper. What a rush that would be!

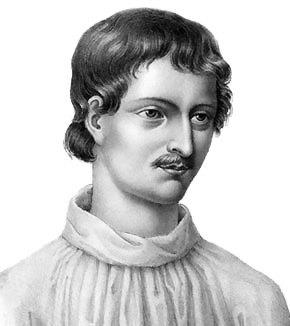

Filippo Bruno was stripped naked, dragged from his prison cell, hung upside down, and burned alive in a market place in Rome

02/19/2020 – It’s Ugly, You Can’t Eat it, and it Looks like Dog Poop!

It’s Ugly, You Can’t Eat it, and It Looks Like Dog Poop:

I may have found my honey Hole!

I have always believed that the measure of an advanced civilization is its capacity to accommodate seemingly useless undertakings working at the fringe of science. The Greeks were into this sort of thing as early as the 6th century BC. The pendulum reached its other apex by the year 1600 when Filippo Bruno was burned at the stake in Rome, partly for advocating that the stars were distant suns surrounded by their own planets and that these planets might foster life of their own. He insisted that the Universe is infinite and could have no center. The anniversary of his execution 420 years ago was February 17th.

An example of Dog Poop Fungus that Karen found the other day as she did your morning bird walked around our place.

I’d rather not think about Bruno’s fate and instead ponder guys like Stan Casto, Professor Emeritus at Mary Hardin Baylor University at Belton, Texas. Among many lifetime achievements, Stan fascinated me by his research on the nasal mites of birds. Now there is an esoteric endeavor for you. One example of his work was the discovery and description of a new mite (Boydaia pheucticola) found in the nasal cavity of the Black-headed Grosbeak. I want to do that! The more fringe it sounds the better I like it.

Maybe I have found my niche. There is a kind of mushroom that Karen and I have located right here on our property (a bit of a stretch to call it a mushroom). Its genus is Pisolithus which means “pea-shaped stone” referring to the internal structures that look like little peas filled with spores.

It would be difficult to dream up a living thing any uglier than this fungus. It goes by names like dead man’s foot, dyemaker’s puffball, Bohemian truffle, horse dung fungus, and in this country, dog turd fungus. Lovingly, I’ll refer to it as the dog poop fungus. What it lacks in beauty it makes up with other fascinating attributes.

Scientists believe this mushroom evolved in Australia. It is adapted to hot dry conditions found there and is well suited for south Texas. It forms a beneficial symbiotic relationship with Eucalyptus trees and has been transported around the world by Eucalyptus trees exported from Australia. However, it can and will form a valuable symbiosis with many other species of trees and now has radiated into as many as 11 new species. The spores of this fungus are used in the planting of landscape trees and in reforestation efforts to provide the young trees with a head start. Evidently, young trees planted in dry infertile soils in the presence of Pisolithus spores grow three times faster.

As one of its names suggests, it can be used for dyeing wool and some studies indicate that it has promise as a cancer treatment. It may have value in carbon sequestration efforts and to enhance the use of plants to clean up environmental contaminants through phytoremediation.

But here’s what excites me. Since they are so damn ugly many researchers avoid them as study subjects because they aren’t sexy. They thrive in climates and soils like we have here in south Texas, and they seem to readily evolve new species. For a man seeking to discover something new, what else could you ask for? I am definitely going to travel down this gopher hole for a while.

Turkey Tail Mushroom (Trametes versicolor) may have value in treating certain cancers and other diseases. I’d say that the jury is out on this and more research is required to be sure. Evidently, it has been used in China for over 2000 years to treat various illnesses. Turkey Tails can be found in Texas, but as always, you need to be absolutely certain that you know what you have before ingesting any mushroom from the wild. See part of its genetic code below.

02/12/2020 – Have you ever Made a Cladogram?

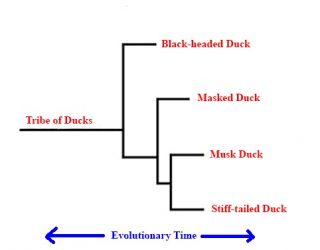

The cladogram above shows the relationship within a tribe of ducks. From left to right, evolutionary time is shown (based on the assumption that evolution marches forward at a slow but steady pace). Imagine a closely-related group of ancient ducks that might be called a tribe. A change in the genetic makeup of this group (possibly a mutation) results in the splitting of the tribe into two distinctly different varieties. One group becomes the Black-headed Duck and the other group goes on to be three separate species, the Masked Duck, the Musk Duck, and the Stiff-tailed Duck. The length of the horizontal lines shows us the relative time between the splitting events that form four new species. Mushrooms, like all other lifeforms, act in this same way.

Humans are visual creatures. A well-organized picture can focus the mind and make understanding much easier. A cladogram is just that sort of picture. Suppose that I am successful in discovering a new-to-science species of mushroom and want to present my evidence to the world. I will need a cladogram similar to the one on the right of this page.

One huge aspect of mushroom science (mycology) that has slapped me in the face since I started this project, is that I simply must learn enough biochemistry to be convincing if I hope to describe a new species. Otherwise, I will need to rely on a recognized mycologist to help me out. Since my last post, that’s about all I have been doing … bathing in the literature of gene sequencing. The weather is not all that conducive to finding mushrooms, so what else do I have to do?

I feel that I have made good progress. I have learned how to take and preserve tissue samples, where to send my samples for analyses, how to compare my gene sequence to an international database of gene sequences, and how to build a cladogram of my results. I have gone through the steps using sequences that I pulled down from the Internet and have been successful. I can’t wait to send off one of my mushroom samples, get my own gene sequence, and see how my specimen fits into the scheme of lifeforms on Earth. Won’t that be fun?

CGATGGTGACTGCGGAGGATCATTAACGAGTTTTGAAACGAGTTGTAGCTGGCCTTCCGAGGCATGTGCACGCTCTGCTCATCCACTCTACCCCTGTGCACTTACTGTAGGTTGGCGTGGGCTCCTTAACGGGAGCATTCTGCCGGCCTATGTATACTACAAACACTTTAAAGTATCAGAATGTAAACGCGTCTAACGCATCTATAATACAACTTTTAGCAACGGATCTCTTGGCTCTCGCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGCGAAATGCGATAAGTAATGTGAATTGCAGAATTCAGTGAATCATCGAATCTTTGAACGCACCTTGCGCTCCTTGGTATTCCGAGGAGCATGCCTGTTTGAGTGTCATGGAATTCTCAACTTATAAATCCTTGTGATCTATAAGCTTGGACTTGGAGGCTTGCTGGCCCTTGTTGGTCGGCTCCTCTTGAATGCATTAGCTCGATTCCGTACGGATCGGCTCTCAGTGTGATAATTGTCTACGCTGTGACCGTGAAGTGTTTTGGCGAGCTTCTAACCGTCCATTAGGACAACTTTTTAACATCTGACCTCAAATCAGGTAGGACTACCCGCTGAACTTAAGCATA

Above, is a 603 base sequence that runs from a beginning location (ITS1) to an ending location (ITS4) along the genome of a common mushroom, the Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor). If a mushroom I find has this string of base pairs between the ITS1 and ITS4 markers, then it has to be a Turkey Tail.

ITS1 and ITS4 have been recognized as markers and have been chosen by mycologists as the genome region most useful for identifying the species of mushrooms. Analyzing these 600 or so bases is what is meant by “barcoding a mushroom.” A widely use rule-of-thumb within the mycological world is that “If the variation between two barcodes is equal to or greater than three percent, then the two barcodes represent two different species. There are arguments that this rule-of-thumb must be applied with great caution.

NOTE: The letters in the sequence represent chemicals that make up the genetic code (G=guanine, C=cytosine, A=adenine, and T=thymine).

All I can say is that I can’t get enough. Learning about and actually doing novel things is thrilling. I hope to leave this world while exploring new ideas. No passive passing for me!

A visit to the Texas Tulip Farm at LaVernia, Texas was exciting. Karen and I drove up to the farm last Wednesday and spent a couple of hours roaming up and down the 34 rows of brightly-colored tulips in various stages of maturity. The parking lot was full and visitors were enjoying the blooms and the nice weather.

01/31/2020 – Tulips Everywhere!

I do like flowers and did enjoy our visit to the Texas Tulip Farm near LaVernia last Wednesday. This is their first year of operation and the place was a big hit. There had to be 50 people there and cars were streaming into the parking lot. The checkout line, where they trim and wrap your tulips was backed up but moving pretty fast. What a neat idea for South Texas. I wish I had thought of it. Do tulips grow around Beeville?

This is the “new-to-me” species of mushroom I collected at the Texas Tulip Farm last Wednesday.

While enjoying the tulips, I could not stop looking for mushrooms. At the end of row four, I spotted a nice one with a brownish cap, very similar to the specimens I’ve been finding around our place near Normanna. I asked permission to collect it and the nice ladies working there graciously said: “Grab it before someone steps right on it and changes it from a toadstool to a pancake.” I dug it out and flipped it over and to my delight, the gills were salmon-colored, totally different from what I expected. Yeah – a new species for me to investigate.

When I got it home, I couldn’t find anything in my field guides that matched what I was seeing. I know how beginning birders feel as they search the paintings in their guide hoping to identify some drab fall warbler. It “ain’t” easy.

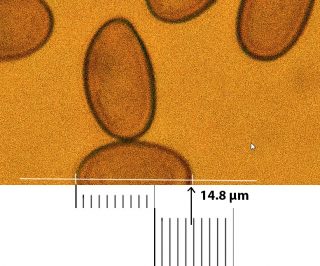

Here is a photo of the spores from the mushroom I collected that the tulip farm. One spore measured 14.8 µm along its widest axis. A human hair can be 200 times wider than a mushroom spore!

Next, I posted the photos and a description to a Facebook group that has 170,000 members ready to assist neophytes like me with a mushroom ID. I got two replies, both suggesting that the species was Volvopluteus gloiocephalus, one of the rare cases of a mushroom with common names (i.e. Big Sheath Mushroom or Rose-gilled Grisette or Stubble Rosegill). I thanked the guys that replied to my inquiry, but my mushroom did not have rose gills, and there were other characteristics that did not match. So I just don’t have a clue what species it is. Oh well – this seems to be a common conclusion in the mushrooms game.

Here is a photo of the spores from the mushroom I collected that the tulip farm. One spore measured 14.8 µm along its widest axis. A human hair can be 200 times wider than a mushroom spore!

By the way, I have been wanting a microscope so I could examine the spores of my mushrooms. Karen, my biologist-wife, said that an instrument with that capability would be really expensive, in the thousands of dollars. This may have been true in the past, but these days, amazing quality can be had at a modest price (thank you China). Just look at the neat photos of mushroom spores I am getting! It is opening up a whole new world.

Jim Yantis loading my old Isuzu Trooper for a trip to Mexico in search of Golden-cheeked Warblers.

01/24/2020 – Islands in the Sand

I have always loved maps. Especially maps of exotic wild places; places where I wanted to don hiking boots and walk through it with my own two feet. In my younger days, Mexico was one of my favorite destinations. My ready companions for these adventures were always my wife Karen and my dear friend Jim Yantis.

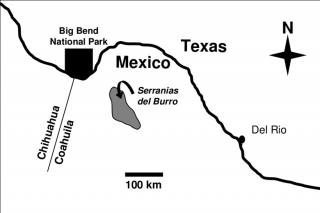

The area in Northern Mexico where Jim Yantis, Karen, and I searched for new populations of Golden-cheeked Warblers.

On a grant from TPWD in the late 1980s, I was helping to document the range of Golden-cheeked Warblers in the Texas Hill Country (listed as endangered in 1990). The entire known breeding range of this species is restricted to Texas. I was struck by the similarity between the terrain of the Edwards Plateau and similar chalky hills I had seen in Northern Mexico. I simply had to go down there and search for Golden-cheeks to see if they were there too. Of course, my wife Karen and Jim Yantis came along for the adventure.

So what does this have to do with mushrooms? It has to do with something I learned from Jim on that trip to Mexico. Jim (who was a Texas Parks and Wildlife biologist) was having great success finding unknown populations of endangered Houston Toads by referring to soil maps. He looked up the soil type where known populations occurred and spend his searching time only in other areas with the same soil type. It seems such an obvious thing to do, but at the time, it was a revelation to me.

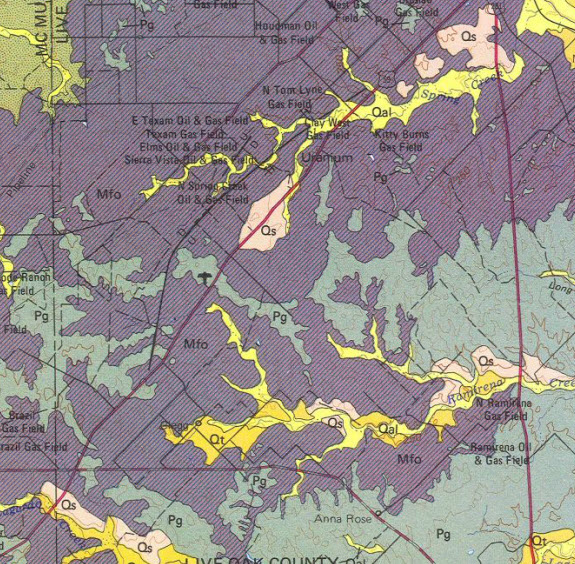

Notice the patches of soil labeled Qs on the geological map of soils west of Three Rivers, Texas. Qs soils are sand sheet deposits created from wind-blown sand of Holocene age.

South Texas is big. Really big. I can’t possibly search all of it for un-discovered mushrooms species. My plan is to visit isolated patches of uncommon soils that may harbor special populations. My hope is that unique species may have evolved in these patches owing to their relative isolation from similar habitats in similar soil types (the Island Effect).

Notice the patches of soil labeled Qs on the geological map of soils west of Three Rivers, Texas. Qs soils are sand sheet deposits created from wind-blown sand of Holocene age.

The map above shows the sort of thing I am looking to explore for mushrooms. These patches of wind-blown sand might create special habitats with enough isolation to foster the evolution of unique species of mushrooms, my equivalent to Jim Yantis’ Houston Toads. I’m waiting for winter to be over (more conducive to mushroom growth) to make a concerted effort to collect mushrooms from Qs soils in my area. Who knows if this plan will up my odds for finding my unknown mushroom. By the way, Karen, Jim, and I did not find Golden-cheeked Warblers in the low hills of the Serranias del Burro in Mexico, but I’ll still bet there are some breeding there.

The photos above show the set up I used to make the spore print. On the left are the two glasses with the mushroom and the paper enclosed. The image on the right is the resulting spore print. Pretty cool!

01/07/2020 – Have you ever made a spore print?

Of course, you know that a mushroom is a fungus. You are likely too young to remember that mushrooms were once considered to be plants. They can grow out of the soil and they do have rigid cell walls like plants, but there are differences.

I’m told that the cell walls of plants are strengthened by cellulose. The material that hardens the cell walls of fungi is chitin, the same stuff that hardens the external skeletons of lobsters and insects. Plants have chlorophyll and fungi don’t. Fungi have to get their energy from organic compounds from living or dead organisms. Fungi were moved from the plant kingdom to their own kingdom in 1969. The cool thing is that they are more closely related to animals than to plants. Maybe that’s why some people make hamburgers with them!

Karen and I went down to Sinton last Friday to photograph a flock of Long-billed Curlews that are spending the winter at Rob & Bessie Welder Park. While walking some of the trails, we discover some good old toadstools growing down in the grass. To my delight, these mushrooms had gills, just the type I had been hoping for.

I found this gilled mushroom at Rob & Bessie Welder Park in Sinton, Texas last Friday. Notice the beautiful chocolate-colored gills.

I dug one out and looked under the cap. It had dense chocolate-brown gills and look very much like the mushrooms we find at H.E.B. These edibles are sold as Portobello mushrooms, but they are also called common mushrooms, white mushrooms, button mushrooms, cultivated mushrooms, table mushrooms, and champignon mushrooms. There is a brown variety (same species Agaricus bisporus) known as Swiss brown mushrooms, Roman brown mushrooms, Italian brown mushrooms, Cremini mushrooms, or Chestnut mushrooms.

I gave up on my bird list and urged Karen to put down her binoculars and race home so I could attempt to identify my toad stoles. She smiled at my obsession while loading up to head for Normanna. One important step for identifying mushrooms is to make a spore print. This sounded like fun and I couldn’t wait to try my luck.

A mature mushroom produces millions of microscopic particles called spores. In the gilled mushrooms, the spores fall downward from the bottom of the cap and are caught by the wind for distribution far and wide. If you remove the stem and place the cap on a clean piece of paper, the spores will fall onto the paper and form a pattern called a spore print. You can’t see the color of a single spore, but with millions on your paper, the spore color is obvious. This color can be a valuable clue to the identity of the species.

I did not want to remove the stem, so I cut a hole in the paper and place the paper and mushroom on top of a water glass. The books say it is a good idea to cover the cap with something to prevent air currents from scattering the spores and blurring the print. I foolishly used another water glass as a cover and that stopped any air currents but created a little greenhouse full of humidity. I got the print, but my specimen was dissolved in the moist enclosure made by the two glasses stacked on each other. Lesson learned.

The spore print began to form within thirty minutes, but I allowed it to form overnight. I ended up with a very nice print that helped me follow a dichotomous key to the genus of Agaricus (same as the grocery store mushrooms). With my present skill level, I could not progress to the species level. There are more than 100 species in the genus Agaricus, and who knows how many more are undiscovered. Maybe I’ve already got my unknown species and am too ignorant to know.

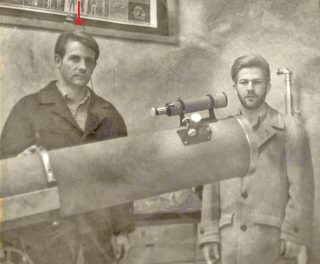

During the 1970s at Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State University), I helped my brother John rebuild an old refracting telescope that we used to learn Astronomy. Both of us have always been interested in science. I’m the one with the red arrow over my head.

01/06/2020 – Will I Get My Comeuppance?

When I was in college as a physics major, I was insufferably arrogant. I looked down on chemistry with the attitude that practitioners were akin to restaurant cooks who followed recipes to achieve outcomes. “Us physicists don’t need no recipes.” We exalted mortals had the insight to calculate all needed outcomes just starting from fundamental principles. In maturity, I soon regretted my cockiness and learned to respect several disciplines I had trivialized in my youth. Chemistry is one.

Since dry conditions and cold weather have retarded the production of mushrooms right now, I have buried myself in the technical literature of mycology. Suppose I really did happen upon an undiscovered and undescribed mushroom, exactly how would I know that and what would I do about it? It appears that no candidate mushroom species can be accepted as new without having first sequenced its DNA. Owing to my early attitude toward chemistry in general and biochemistry in particular, this was not good news to me. Back in 2007, about 100 mycologists got together in conference and decided that the best way to make the final judgment about whether a fungus is new would be to sequence a segment of its DNA; its “ITS” or Internal Transcribed Spacer. What I know about sequencing DNA can be written between the double EEs in the word between. Learning about mushrooms will not be enough. Either I must also learn some very esoteric biochemistry or I will need to find a specialist that is willing to forgive my college attitude and allow me to watch over his or her shoulder while the real work is done.

BentoLab DNA Analyser (A Kickstarter funded project) can be pre-ordered for around $1600. This little box puts the world of DNA Barcoding onto your kitchen table and in your own hands.

Interestingly though, there is an underground movement of people working in garages and basements trying to take techniques of gene splicing and DNA sequencing out of the exalted domain of big tech and university laboratories and bring it to the little guys. Echoing the origins of microcomputers, young entrepreneurs are struggling to make puppies glow in the dark and crowdfunding small businesses with aims to put DNA analysis in the hands of common people for under $1000. I just watched a fascinating YouTube video of a young New Zealander extracting DNA from an unknown substance, snipping it into small segments, amplifying it, and sequencing it with a laptop and a small microchip, and then comparing his sequence to a massive online database, and identifying the substance as puréed tomatoes. All this was done, start to finish, on a desk, in front of an audience, while doing a PowerPoint presentation, in less than one hour (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHCAb-PAqUI)!

I felt very blessed to have lived during the microcomputer revolution. I think a similar revolution is taking place right now. Most of us don’t know it exists, but 20 years from now, the foundations of our world will have changed.

Have you ever heard of Robert Ridgway? This is one of the plates from Ridgway’s Color Standards and Color Nomenclature. There are 1,115 colors described in the volume. Can you imagine thinking up that many unique color names?

12/26/2019 – All Those Colors!

Robert Ridgway could have worked for the Benjamin Moore Company making up names for paint chips. Instead, Ridgway was the curator of birds at the United States National Museum until his death in 1929. Over his career, he may have described more new species of American birds than any other ornithologist.

My first contact with the works of Ridgway was while I attended graduate school at Texas A&M. Even though I was there to study cosmic rays, my love for birds caused me to spend considerable time mingling with the bird people, a short stroll over from the Physics Building. I was fascinated by the thousands of study skins of birds that were lodged in the basement of the Heap Building. I watched and marveled as the Curator of Birds, Dr. Keith Arnold, skinned, prepared and described newly collected specimens. As he wrote up his description of some patch of color on the specimen, he would pull down his copy of Ridgway’s Color Standards and Color Nomenclature which contained 1,115 cleverly named color plates, exactly like paint chips you might find at Walmart. Keith was making sure that readers 200 years from then would know exactly the color of that bird’s eye ring while it was fresh and lying on his preparation table. Only 500 of Ridgway’s books of standard colors were ever printed and remaining copies are precious and hoarded by scientists around the world. Copies were (and are) treasured by mycologists as well.

If I am to one day find an undescribed species of mushroom, I will need to collect and preserve specimens of the fruiting bodies of fungi I find here in South Texas. I remembered Ridgway and thought I might acquire a copy to help me write descriptions of mushrooms. NOT! Even worn-out volumes of Ridgway’s book are selling on eBay for over $600.

This is a photo of a bracket fungus I discovered at Veteran’s Memorial Park in Beeville, Texas. I have not yet tried to identify it to species.

I have decided to go modern and use a digital method of describing and preserving those subtle colors found on fresh mushrooms. I am into photography, so I have a device that calibrates the colors on my computer monitor. If I make images of my mushrooms against of standard Kodak R-27 gray card, I can be sure that the colors of my images will be very close to the “real” colors of the fresh specimens. In most good photo processing software (like Adobe Photoshop), there is a color picker tool that can be used to measure the Hue, Saturation, and Value (HSV) of colors in an image. Photoshop actually uses brightness rather than Value, but they are the same thing.

Notice the small green circle on the cap of an unidentified bracket fungus I found at Veteran’s Memorial Park in Beeville recently (see above). By using my eyedropper tool in Photoshop, I am able to determine that the HSV numbers for the color within the circle are 21, 50, and 74 respectively. Although this color does not have an official name, by invoking the spirit of Ridgway, I christen this color “Elephant Dung Brown.” Coming up with a color name for part of a mushroom cap could be my only contribution to the knowledge-basic of mycologists!

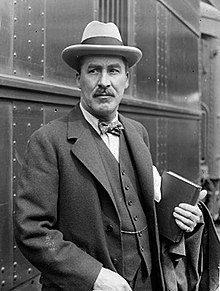

Carnarvon asked, “Can you see anything?” Carter replied with the famous words: “Yes, wonderful things!

12/18/2019 – First Identified Mushroom

I am excited to report a small breakthrough in my quest to learn mushroom identification. With a little starting help, I was able to sort out the species of a mushroom I collected in Refugio a couple of days ago. In a small way, I felt like Howard Carter as he peered through a hole into Tutankhamun’s tomb for the first time and said: “I see wonderful things!”

I invited my friend John West, to ride along with me on a venture down to Lions/Shelly Park at Refugio. It is a super neat little park on a resaca of the Mission River and I speculated that there might be some mushrooms to be found there. It was a warm beautiful day, so mushrooms or not, it would be fun.

The park was damaged badly during hurricane Harvey and is not officially open to the public. However, when we arrived, there were people strolling around the trails and enjoying the warm day. I figured that if the locals were using the park, so could we.

John took up a position near the creek hoping to get some bird photos, while I began a search for mushrooms. With eyes looking down, I started a slow search along the water’s edge hoping to spot some fruiting fungi.

Top section, mushroom cap, middle section, gills, and bottom section, spore print.

Within two minutes, I found my first mushrooms! They were pale white and growing from the sides of fallen dead limbs of black willow trees. I had no idea what species they might be.

Not far away, I found a second type of mushroom. I knew they were not the same species because the first ones had gills and the others had pores instead of gills. I collected samples of both types and secured them in the back seat of my truck. John strolled up to see what I had and we decided to celebrate by treating ourselves to ice cream at Dairy Queen before heading back to Beeville with my little treasures.

From my reading, I knew that my next step would be to photograph the samples and make spore prints. What is a spore print you ask? Mushrooms produce massive numbers of spores that fall from either their gills or pores. If you lay the cap of a fresh mushroom onto a clean surface, the spores will fall onto the surface and, over several hours, cover it with spores. The color of the spore print can be a valuable clue to mushroom identity.

I used a microscope slide for my surface and allowed my samples to sit on the slides overnight. The next morning I had a beautiful white spore print from the gilled mushroom but nothing from the one with pores. None of my samples were fresh, so I suppose that I was lucky to get a print from just one.

Next, I uploaded my photos and a description of the gilled mushroom to a Facebook group called Texas Mushroom Identification. There are about 4000 members of the group and many are experts at mushroom identification. I suspect that many of the members forage for edible wild mushrooms as a hobby. Certain mushrooms are deadly poison and not being certain of the species before ingesting one can send you to a slow, painful and sure death. A few people have been saved from their mistakes with emergency liver transplants. If I’m ever brave enough to eat one I’ve found, you can be sure I will know what it is before swallowing a piece.

Within a few minutes, a kind member of the group told me that I had found an oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus! I suppose I will need to learn these Latin names since most mushrooms don’t have a common name at all. That will be a subject for a future post.

Armed with this suggested identification, I referred to a set of dichotomous keys (more about these later) by Michael Kuo, known as the Mushroom Expert on the Internet (MushroomExpert.com). If you have never used a dichotomous key, they can be terribly frustrating for a beginner. You start down a long list of paired questions about features you can examine from your collected sample, and at the end of the chain, you come to the species identity. Sounds easy, but it is really difficult to get through one of these keys.

As a learning exercise, I worked the key backward from my suggested species name and verified every single feature that needed to be part of my sample and, sure enough, it was Pleurotus ostreatus. It turns out that oyster mushrooms are one of the most sought after wild mushrooms because they are safe and are said to be great eating. I understand that they can be bought in grocery stores in the larger cities. If I find some fresh ones in the future, I may break my “don’t eat” rule and fry some up for a try.

It does feel really good to have opened a small crack into the world of wild mushrooms. I am excited.