Lars Jonsson, a Swedish bird artist, works with a group of local artists to improve their skills at drawing birds. Lars prefers to draw and paint in the outdoors using wild birds as his models. Robert Benson photo.

How hard can it be? An oval for the body, a circle for the head, a triangle for the beak and you’ve drawn a bird. Or so I thought.

I found out differently when I attended Lars Jonsson’s Master Class in bird painting this past weekend. Drawing and painting birds, especially in the wild, requires patience, a good eye, and above all, talent. I was sadly lacking in all three.

Lars Jonsson, a renown Swedish artist, has been painting birds since he was four. He had his first professional show when he was just fifteen. For the past fifty years, he has produced thousands of paintings of birds, nearly all of them painted in the field. Lars was at the San Domingo Ranch in Bee County for a recent conference on wild birds. He offered to show local artists (and one non-artist) the techniques he uses to produce his exquisite paintings of birds.

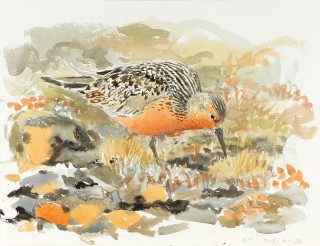

Lars Jonsson is a master at painting birds in their natural settings. This Red Knot is pictured on its Arctic tundra breeding grounds. Lars Jonsson painting.

Jonathan Wood, who does a show called “Extreme Raptors,” lent us an arctic Gyrfalcon for a model. The Gyrfalcon posed nicely. Wisely, Lars Jonsson suggested that we see what we could do on our own. The resulting drawings and watercolors varied considerably within the class. Most of the paintings were quite good. My Gyrfalcon looked like a wet and bedraggled chicken, however.

Clearly, I had a lot to learn. I paid close attention to Lars’ demonstration of how to draw a bird. He began with the bones of a bird. The skeleton is the framework to which muscles and feathers attach. Once you realize how the bones fit together, you can sketch a much more realistic bird.

An albino laughing gull with the sun behind it offers a rare glimpse in to the structure of a bird’s wing. The short bone coming from the bird’s body is analogous to our upper arm bone. At the elbow (downward bend) it joins the two lower arm bones. The wrist and hand bones are modified to form the outermost section of the limb. The main flight feathers are attached to the bird’s “hand.” Robert Benson photo.

For instance, the bones of the wing are pretty much the same as the ones in our arm and hand. There is the humerus, the upper arm bone which is attached to the ulna and radius at the elbow. These lower arm bones are elongated in birds. The wrist and hand bones have been modified and fused to make the outer part of the wing. The main flight feathers, called the primaries, grow out of the “hand” bones of the wing. The secondary flight feathers grow out from the side of the ulna. The tertiaries grow from the humerus. Feathers that cover the bases of these flight feathers are called “coverts.”

If you draw these feathers in as groups, you build up a convincing bird. Lars cautioned us against drawing in individual feathers, at least not until you have the basic bird drawn. Of course, there is a lot more to producing a work of art than this first sketch. But this is how you should start.

Lars Jonsson is one of many great bird artists who have published a field guide. His Birds of Europe with North Africa and the Middle East (1999) is considered the best for that region. Field guides are meant to help the birdwatcher identify birds out in nature. Distinctive characteristics of each species are pointed out, sometimes in the text, and often with arrows. Roger Tory Peterson, author and artist of many American field guides, pioneered the use of rather stylized side views of the birds, with arrows pointing to key characteristics.

A number of bird field guides are available for the United States. I prefer those with paintings of birds rather than photographs. A painting can show all the features of the bird, including some that may be blurred or covered up in a photograph. It is also possible to put several birds on a single page for comparison. Besides Roger Tory Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds East of the Rockies, there is one for the western birds, and one specific to Texas. These are the classics.

National Geographic published a very popular Field Guide to the Birds of North America in 1983. It has been reprinted and revised a number of times since then. Its artwork is detailed, crisp and very clear. It is my husband’s favorite field guide. I have become partial to The Sibley Guide to Birds published by the National Audubon Society in 2000. I think I just like David Allen Sibley’s style of painting.

If you are in the market for a field guide, look over your options and choose one (or more) that you like and will use. Keep in mind that a guide should be portable, so smaller is better. Along those lines, you might consider downloading one of the apps for your i-Phone. But that is a subject for a whole ‘nother column!

ESSAY BY KAREN L. P. BENSON

If you would like to receive Karen’s Nature Essays by email, please signup here.