Net-leaf Hackberry, named for the raised network of veins seen on the underside of its leaves, is a common tree in South Texas. It is the larval food for a number of butterfly species. The berries ripen in the fall and persist on the tree providing plentiful winter food for birds. Karen Benson photo.

05 Aug 2016 – Hackberry: A Gem of a Weed

I had gone past the thorny stretch of brush many times. I never paid much attention to it until this summer when I noticed it was loaded with yellow berries. Had it been producing this much fruit every year? Or was this a record year for hackberries?

The berries looked like they might be good to eat. I knew mockingbirds love them. However, I checked the field guides to make sure that the berries were not poisonous before I tried one. I picked one of the small golden fruits from the spiny shrub and popped it in my mouth. It was fleetingly sweet and fruity and then quite crunchy. I could tell it had a pretty big seed inside a thin layer of juicy pulp. Still, it tasted good. If you gathered enough of them, they might make an interesting jam. Or perhaps a crunchy-sweet dried fruit bar.

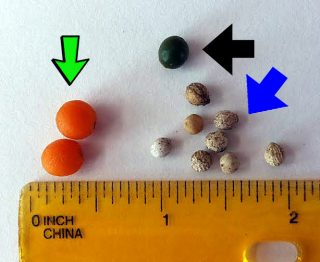

Hackberry fruits are not true berries but drupes. A drupe contains a single hard seed surrounded by juicy pulp. Net-leaf Hackberry fruits (black arrow) are mostly still green at this time while Spiny Hackberry fruits (green arrow) are a ripe golden yellow. The stony seeds (blue arrow) have mineralized seed coats made of opal and calcium carbonate. Karen Benson photo

This shrubby hackberry is Celtis pallida, or Spiny Hackberry. Most folks around here call it Granjeno. Spiny Hackberry is one of the most valuable wildlife food plants in the brush. White-tailed Deer browse on the stems and leaves. The berries provide food for doves, quail, wrens, cardinals, pyrrhuloxias, mockingbirds, thrashers and green jays. Small mammals including coyotes, raccoons, and rabbits also relish the berries. The zigzagged branches with stout, paired thorns provide a safe haven for nesting, roosting and loafing. Quail appreciate the dense cover Spiny Hackberry thickets offer. And the leaves are the larval food for a number of butterfly species.

Spiny Hackberry is not the only hackberry around, however. There are two trees in the genus as well: Net-leaf Hackberry (Celtis reticulata) and Sugarberry (Celtis laevigata). Both are common in Texas and indeed in the United States. These are trees that go unnoticed because they lack “showy flowers, striking form, or fall color.” According to Matt Warnock Turner in his Remarkable Plants of Texas (2009), the hackberry “is ragged in appearance with crooked branches and warty trunks.” Understandably, the hackberry is “rarely included in landscaping plans, and to most city folk, it is an unremarkable denizen of alleyways and fencerows.” Even in the countryside, it is often ignored, until a storm breaks its weak limbs or blows it over.

The tree’s worst feature is its habit of reseeding itself everywhere. Have you ever been frustrated by trying to pull hackberry seedlings out of your flowerbeds? It is no wonder that many people consider hackberry trees to be weeds.

Matt Turner points out: “The flipside of a weed is a tough and dependable survivor.” Hackberries are fast growing, drought-tolerant and not at all picky about soil type. They provide shade where nothing else can grow. And they can be fairly attractive trees.

Best of all, the Net-leaf Hackberry and the Sugarberry trees, like the Spiny Hackberry shrub provide abundant food for wildlife. Their leaves feed the caterpillars of many butterflies including American Snout, Mourning Cloak, Question Mark, and Tawny and Hackberry Emperors. The berries persist on the trees well into winter and provide a critical food for both migratory and resident birds.

Humans have long availed themselves of the fruit of hackberries. We know this from pollen found in human coprolites dating to 500BC. Even older archaeological digs contain quantities of the stony little hackberry seeds. Historically, many Native American tribes ground the berries to a paste, mixed the paste with fat, and roasted or dried it. The pulp provided a sweet taste and the hard seeds provided a nutty crunch.

About that crunch: What is it that makes those seeds so hard? A hackberry isn’t a “berry” at all, but a drupe. A drupe has a single stony pit in the center of the pulp, just like a plum or peach. A hackberry drupe is like a tiny plum. The difference is the hackberry pit is indeed “stony,” that is, it is made of minerals and not wood.

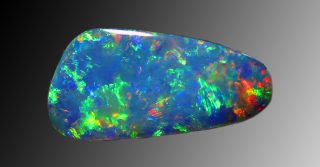

Precious opal displays flashes of color that make it valuable as a gemstone. Opal is a mineral made of silica spheres and water molecules. In some specimens, the regular arrangement of silica spheres diffracts light to produce a “play of color.” Wikimedia commons photo.

I recently read Lab Girl (2016) by Hope Jahren. She recounts doing research on hackberry seeds. She discovered that she could dissolve away part of the hard seed coat with acid. The dissolvable mineral was calcium carbonate, as is found in many seashells and limestone. A lattice-like framework of some other mineral remained. Using an X-ray diffraction machine, she determined the other mineral was opal! Opal is a mineral (some geologists say it is a mineraloid) made of hydrated amorphous silicon dioxide; it has microscopic spheres of silica aggregated into layers surrounded by water molecules. The orderly pattern of the silica spheres diffract the light and give precious opals that lovely “play of color” we think of when we think of opals. Although the hackberry opal is not gemstone quality opal, it is still fascinating to think of a plant protecting its embryos in seed coats made of rock! And not just any rock, but a mineral that is also used as a gemstone!

Spiny Hackberry has paired thorns at each node making it a well-armed component of the brush. Its berries provide food for many birds and small mammals. Its leaves are food for deer and butterfly larvae. Robert Benson photo.

It is the opal, and to some extent, the calcium carbonate, in the hackberry seed coats that make them so valuable in archaeology. They can last for thousands of years without decomposing. Carbon-14 in the calcium carbonate can be “carbon-dated” and thus the age of the archaeological site determined.

You may remember seeing hackberry seeds as a child. My brothers and I used to make “pretend towns” in the sandy areas of our driveway. We preferred to play in the shade of the big hackberry. All around in the sand were tiny round white seeds that we used as “pretend cantaloupes” in our “pretend farms.” We loaded them up in our little trucks and carried them to our “pretend markets.”

Sixty years later, I finally find out those tiny “pretend cantaloupes” were the seeds of the hackberry tree that shaded us!

If you would like to offer comments, please click through to the discussion page