Narrow-leaf Gayfeather is a fall-blooming wildflower common to south Texas. Swaths of the purple spikes can cover roadsides and pastures. Robert Benson Photo.

Fall’s Purples and Golds Advertise Nectar

Our South Texas trees may not offer much in the way of fall color, but our autumn-blooming wildflowers sure do. Perhaps you have noticed those patches of purple and stands of yellow-gold along our highways? Those are our area’s seasonal color.

Late season wildflowers have to hurry up and make seed before the cold sets in. So they must attract pollinators to get those seeds fertilized. Most flowers blooming this time of year produce a lot of nectar to bribe bees and butterflies to visit them. And to advertise that they have nectar, they use color and fragrance, but especially color.

Bright golds and yellows, and vibrant purples shout out to the insect world that the flowers are “serving food.” Just like you and I can spot those “golden arches” of MacDonalds a mile away, so can the bees and butterflies locate sources of their fast food by color.

The yellow wildflower that grabs attention is the Tall Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis). This goldenrod usually forms colonies of plants from underground roots. Most often, you will see a group of twenty or more plants, up to six-feet high and with large terminal clusters of golden flowers. Each goldenrod flower head is only about a quarter of an inch across. On close focus it looks like a tiny sunflower! Every terminal cluster will have hundreds of these tiny flower heads.

Tall Goldenrod has panicles of hundreds of tiny golden flower heads. This nectar producer is a magnet for bees and butterflies in the fall. Karen Benson Photo.

There are several species of goldenrods and they often hybridize. The specimen I examined had decidedly “raspy” leaves. The roughness was intensified by rubbing the leaf backwards from the tip. The leaf felt like a cat’s tongue! Under the microscope, I could see the leaf surface was covered with tiny, translucent thorns that curved backwards. This characteristic indicated that this goldenrod was Solidago radula. But the plant was easily over five feet tall and S. radula averages only two-and-a-half feet. I am pretty sure my specimen was some sort of hybrid.

It is not surprising to me that goldenrods are often hybrids. The species all bloom from September to November and all of them attract pollinators like crazy. A busy bee could easily visit several different goldenrods while gathering nectar. As a bee rummages among the flower heads, it could readily transfer pollen to different goldenrod species.

Another wildflower that blankets pastures and roadsides this time of year is the purple, Narrow-leaf Gayfeather (Liatris mucronata.) Gayfeather has heads of three to six individual flowers. The heads grow along a slender spike that can be up to three feet high. The spikes of gayfeather give our roadsides a purple haze above the lower, green vegetation.

Gayfeather, like goldenrod, produces lots of nectar. It is usually covered by bees and butterflies. Bees, as you know, convert nectar to honey and store the honey for the hive to live on during the winter. Butterflies, on the other hand, must store the nectar as fat reserves within their own bodies. This fat storage is particularly important for butterflies that over-winter as adults.

The most famous over-wintering butterfly is the Monarch Butterfly. A Monarch only lives about one month, during which it lays the eggs for the next generation. Four or five generations are produced during the spring and summer on their breeding grounds. The last generation of the summer is special. It can survive the winter. But it must go to a place where the winter is cold (but not below 19 degrees F) and dry. In other words, it must migrate to a very special place.

Most of the Monarchs we see in Texas in the fall are in migration. They are on their way to their famous wintering grounds in the Oyamel Fir forests of mountainous central Mexico. These individuals hatched out in the central prairies and farmlands of North America. In late August, these adults (destined to live for 9 months) start their 2,000 mile journey south.

Monarch Butterflies imbibe nectar heavily at fall-blooming flowers. They feed on as much nectar as they can while they travel. They must put on enough weight (as lipids within their abdomens) in order to first, make the journey, and second, to survive the dry cold of the winter in the fir forests. Nectar from goldenrod and gayfeather, as well as other fall composite flowers, give the migrating Monarchs the food reserves they need.

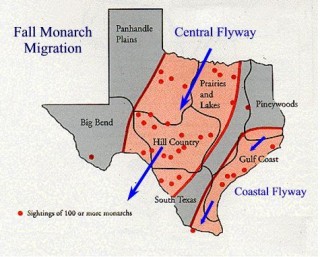

Migrating Monarchs reach Texas in early October. Most follow the central flyway across the middle of Texas, but some take the coastal flyway. Along these flyways, hundreds, sometimes thousands of Monarchs can be seen in a single day. Clouds of butterflies often settle down on a patch of wildflowers to feed.

Documented sightings and tagged butterflies have shown that Monarch Butterflies funnel through Texas in the fall. There are two distinct flyways: the Central and the Coastal. In these areas, hundreds of Monarchs can be seen flying south to their wintering grounds in the mountains of central Mexico. Texas Monarch Watch Map.

Bee County is just between the two main flyways. Consequently, we see a few migrating Monarchs but in much fewer numbers than on the flyways proper. The butterflies reach our area beginning around October 15th and are gone by October 27th. The peak of migration for our latitude is on October 23rd. Each butterfly is on its way to Mexico and it needs to fatten up.

So, plant lots of nectar-rich flowers in your gardens for the Monarchs. And preserve the goldenrods and gayfeathers along our roadways. You, and the butterflies, will be glad you did!

If you would like to offer comments, please click through to the discussion page